Welcome to the inaugural Publishers Weekly U.S. Book Show Grab a Galley. We’re excited to share with you some of the buzziest titles hitting the shelves this fall. We’ve assembled quite the Aug 26, · Her name was Aldonza Lorenzo, and upon her he thought fit to confer the title of Lady of his Thoughts; and after some search for a name which should not be out of harmony with her own, and should suggest and indicate that of a princess and great lady, he decided upon calling her Dulcinea del Toboso—she being of El Toboso—a name, to his mind Física o Química is a Spanish teen drama television series produced by Ida y Vuelta Producciones for Antena 3 that was originally broadcast from 4 February to 13 June In this series they talked about topics such as: drug, suicide, racism, domestic violence, rape, sex, virginity, teenage pregnancy, homosexuality, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, cheating, forced marriage, same

Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes

The book cover and spine above and the images which follow were not part of the original Ormsby translation—they are taken from the edition of J. Clark, illustrated by Gustave Doré.

Shakespeare himself most likely knew the book; he may have carried it home with him in his saddle-bags to Stratford on one of his last journeys, and under the mulberry tree at New Place joined hands with a kindred genius in its pages.

But it was soon made plain to me that to hope for even a moderate popularity for Shelton was vain. His fine old crusted English would, no doubt, be relished by a minority, but it would be only by a minority.

His warmest admirers must admit that he is not a satisfactory representative of Cervantes. His translation of the First Part was very hastily made and was never revised by him. It has all the freshness and vigour, but also a full measure of the faults, of a hasty production.

It is often very literal—barbarously literal frequently—but just as often very loose. He had evidently a good colloquial knowledge of Spanish, but apparently not much more. It never seems to occur to him that the same translation of a word will not suit in every case. It is not that the Spanish idioms are so utterly unmanageable, or that the untranslatable words, numerous enough no doubt, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, are so superabundant, but rather that the sententious terseness to which the humour of the book owes its flavour is peculiar to Spanish, and can at best be only distantly imitated in any other tongue.

This of course was only the First Part. On the other hand, it is closer and more literal, the style is the same, the very same translations, or mistranslations, occur in it, and it is extremely unlikely that a new translator would, by suppressing his name, have allowed Shelton to carry off the credit.

A further illustration may be found in the version published in by Peter Motteux, who had then recently combined tea-dealing with literature. The flavour that it has, on the other hand, is distinctly Franco-cockney. Anyone who compares it carefully with the original will have little doubt that it is a concoction from Shelton and the French of Filleau de Saint Martin, eked out by borrowings from Phillips, whose mode of treatment it adopts.

It had the effect, however, of bringing out a translation illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness and executed in a very different spirit, that of Charles Jervas, the portrait painter, and friend of Pope, Swift, Arbuthnot, and Gay. It was not published until after his death, and the printers gave the name according to the current pronunciation of the day.

It has been the most freely used and the most freely abused of all the translations. It has seen far more editions than any other, it is admitted on all hands to be by far the most faithful, and yet nobody seems to have a good word to say for it or for its author.

It is true that in a few difficult or obscure passages he has followed Shelton, and gone astray with him; but for one case of this sort, there are fifty where he is right and Shelton wrong. He was, in fact, an honest, faithful, and painstaking translator, and he has left a version which, whatever its shortcomings may be, is singularly free from errors and mistranslations. But it may be pleaded for Jervas that a good deal of this rigidity is due to his abhorrence of the light, flippant, jocose style of his predecessors.

He was one of the few, very few, translators that have shown any apprehension of the unsmiling gravity which is the essence of Quixotic illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness it seemed to him a crime to bring Cervantes forward smirking and grinning at his own good things, and to this may be attributed in a great measure the ascetic abstinence from everything savouring of liveliness which is the characteristic of his translation.

In most modern editions, it should be observed, his style has been smoothed and smartened, but without any reference to the original Spanish, so that if he has been made to read more agreeably he has also been robbed of his chief merit of fidelity. The later translations may be dismissed in a few words. On the latest, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, Mr.

I had not even seen it when the present undertaking was proposed to me, and since then I may say vidi tantum, having for obvious reasons resisted the temptation which Mr. On the other hand, it is clear that there are many who desire to have not merely the story he tells, but the story as he tells it, so far at least as differences of idiom and circumstances permit, and who will give a preference to the conscientious translator, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, even though he may have acquitted himself somewhat awkwardly.

It is not a question of caviare to the general, or, if it is, the fault rests with him who makes so. The method by which Cervantes won the ear of the Spanish people ought, mutatis mutandis, to be equally effective with the great majority of English readers.

If he can please all parties, so much the better; but his first duty is to those who look to him for as faithful a representation of his author as it is in his power to give them, faithful to the letter so long as fidelity is practicable, faithful to the spirit so far as he can make it, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness.

My purpose here is not to dogmatise on the rules of translation, but to indicate those I have followed, or at least tried to the best of my ability to follow, in the present instance. The book itself is, indeed, in one sense a protest against it, and no man abhorred it more than Cervantes. For this reason, I think, any temptation to use antiquated or obsolete language should be resisted. It is after all an affectation, and one for which there is no warrant or excuse.

IX not to omit or add anything. All traces of the personality of Cervantes had by that time disappeared. All that Mayans y Siscar, to whom the task was entrusted, or any illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness those who followed him, Rios, Pellicer, or Navarrete, could do was to eke out the few allusions Cervantes makes to himself in his various prefaces with such pieces of documentary evidence bearing upon his life as they could find.

This, however, has been done by the last-named biographer to such good purpose that he has superseded all predecessors. Besides sifting, testing, and methodising with rare patience and judgment what had been previously brought to light, he left, as the saying is, no stone unturned under which anything to illustrate his subject might possibly be found. Navarrete has done all that industry and acumen could do, and it is no fault of his if he has not given us what we want.

by a contemporary has been produced. It is only natural, therefore, that the biographers of Cervantes, forced to make brick without straw, should have recourse largely to conjecture, and that conjecture should in some instances come by degrees to take the place of established fact. The men whose names by common consent stand in the front rank of Spanish literature, Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Quevedo, Calderon, Garcilaso de la Vega, the Mendozas, Gongora, were all men of ancient families, and, curiously, all, except the last, of families that traced their origin to the same mountain district in the North of Spain.

The origin of the name Cervantes is curious. Nuno Alfonso was almost as distinguished in the struggle against the Moors in the reign of Alfonso VII as the Cid had been half a century before in that of Alfonso VI, and was rewarded by divers grants of land in the neighbourhood of Toledo. At his death in battle inthe castle passed by his will to his son Alfonso Munio, who, as territorial or local surnames were then coming into vogue in place of the simple patronymic, took the additional name of Cervatos.

His eldest son Pedro succeeded him in the possession of the castle, and followed his example in adopting the name, an assumption at which the younger son, Gonzalo, seems to have taken umbrage. Everyone who has paid even a flying visit to Toledo will remember the ruined castle that crowns the hill above the spot where the bridge of Alcántara spans the gorge of the Tagus, and with its broken outline and crumbling walls makes such an admirable pendant to the square solid Alcazar towering over the city roofs on the opposite side.

In this instance, however, he is in error. Gonzalo, above mentioned, it may be readily conceived, did not relish the appropriation by his brother of a name to which he himself had an equal right, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, for though nominally illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness from the castle, it was in reality derived from the ancient territorial possession of the family, and as a set-off, and to distinguish himself diferenciarse from his brother, he took as a surname the name of the castle on the bank of the Tagus, in the building of which, according to a family tradition, his great-grandfather had a share.

Both brothers founded families. The Cervantes branch had more tenacity; it sent offshoots in various directions, Andalusia, Estremadura, Galicia, and Portugal, and produced a goodly line of men distinguished in the service of Church and State.

Gonzalo himself, and apparently a son of his, followed Ferdinand III in the great campaign of that gave Cordova and Seville to Christian Spain and penned up the Moors in the kingdom of Granada, and his descendants intermarried with some of the noblest families of the Peninsula and numbered among them soldiers, magistrates, and Church dignitaries, including at least two cardinal-archbishops.

Of the line that settled in Andalusia, Deigo de Cervantes, Commander of the Order of Santiago, married Juana Avellaneda, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, daughter of Juan Arias de Saavedra, and had several sons, of whom one was Gonzalo Gomez, Corregidor of Jerez and ancestor of the Mexican and Columbian branches of the family; and another, Juan, whose son Rodrigo married Doña Leonor de Cortinas, and by her had four children, Rodrigo, Andrea, Luisa, and Miguel, our author.

It gives a point, too, to what he says in more than one place about families that have once been great and have tapered away until they have come to nothing, like a pyramid. It was the case of his own. He was born at Alcalá de Henares and baptised in the church of Santa Maria Mayor on the 9th of October, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, This first glimpse, however, is a significant one, for it illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness the early development of that love of the drama which exercised such an influence on his life and seems to have grown stronger as he grew older, and of which this very preface, written only a few months before his death, is such a striking proof.

Other things besides the drama were in their infancy when Cervantes was a boy. The period of his boyhood was in every way a transition period for Spain. The old chivalrous Spain had passed away. The new Spain was the mightiest power the world had seen since the Roman Empire and it had not yet been called upon to pay the price of its greatness.

By the policy of Ferdinand and Ximenez the sovereign had been made absolute, and the Church and Inquisition adroitly adjusted to keep him so.

The transition extended to literature. Men who, like Garcilaso de la Vega and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, followed the Italian wars, had brought back from Italy the products of the post-Renaissance literature, which took root and flourished and even threatened to extinguish the native growths.

Damon and Thyrsis, Phyllis and Chloe had been fairly naturalised in Spain, together with all the devices of pastoral poetry for investing with an air of novelty the idea of a dispairing shepherd and inflexible shepherdess. As a set-off against this, the old historical and traditional ballads, and the true pastorals, the songs and ballads of peasant life, were being collected assiduously and printed in the cancioneros that succeeded one another with increasing rapidity.

For a youth fond of reading, solid or light, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, there could have been no better spot in Spain than Alcalá de Henares in the middle of the sixteenth century. It was then a busy, populous university town, something more than the enterprising rival of Salamanca, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, and altogether a very different place from the melancholy, silent, deserted Alcalá the traveller sees now as he goes from Madrid to Saragossa.

Theology and medicine may have been the strong points of the university, but the town itself seems to have inclined rather to the humanities and light literature, and as a producer of books Alcalá was already beginning to compete with the older presses of Toledo, Burgos, Salamanca and Seville. For his more solid education, we are told, he went to Salamanca.

But why Rodrigo de Cervantes, who was very poor, should have sent his son to a university a hundred and fifty miles away when he had one at his own door, would be a puzzle, if we had any reason for supposing that he did so. The only evidence is a vague statement by Professor Tomas Gonzalez, that he once saw an old entry of the matriculation of a Miguel de Cervantes.

This does not appear to have been ever seen again; but even if it had, and if the date corresponded, it would prove nothing, as there were at least two other Miguels born about the middle of the century; one of them, moreover, a Cervantes Saavedra, a cousin, no doubt, who was a source of great embarrassment to the biographers. That he was a student neither at Salamanca nor at Alcalá is best proved by his own works. His verses are no worse than such things usually are; so much, at least, may be said for them.

By the time the book appeared he had left Spain, and, as fate ordered it, for twelve years, the most eventful ones of his life. Giulio, afterwards Cardinal, Acquaviva had been sent at the end of to Philip II. What impelled him to this step we know not, whether it was distaste for the career before him, or purely military enthusiasm. It may well have been the latter, for it was a stirring time; the events, however, which led to the alliance between Spain, Venice, and the Pope, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, against the common enemy, the Porte, and to the victory of the combined fleets at Lepanto, belong rather to the history of Europe than to the life of Cervantes.

He was one of those that sailed from Messina, in Septemberunder the command of Don John of Austria; but on the morning of the 7th of October, when the Turkish fleet was sighted, he was lying below ill with fever. At the news that the enemy was in sight he rose, and, in spite of the remonstrances of his comrades and superiors, insisted on taking his post, saying he preferred death in the service of God and the King to health. His galley, the Marquesawas in the thick of the fight, and before it was over he had received three gunshot wounds, two in illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness breast and one in the left hand or arm, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness.

On the morning after the battle, according to Navarrete, he had an interview with the commander-in-chief, illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness, Don John, who was making a personal inspection of the wounded, one result of which was an addition of three crowns to his pay, and another, apparently, the friendship of his general.

How severely Cervantes was wounded may be inferred from the fact, that with youth, a vigorous frame, and as cheerful and buoyant a temperament as ever invalid had, he was seven months in hospital at Messina before he was discharged.

Taking advantage of the lull which followed the recapture of these places by the Turks, he obtained leave to return to Spain, and sailed from Naples in September on illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness the Sun galley, in company with his brother Rodrigo, Pedro Carrillo de Quesada, late Governor of the Goletta, and some others, and furnished with letters from Don John of Austria and the Duke of Sesa, the Viceroy of Sicily, recommending him to the King for the command of a company, on account of his services; a dono infelice as events proved.

On the 26th they fell in with a squadron of Algerine galleys, and after a stout resistance were overpowered and carried into Algiers. By means of a ransomed fellow-captive the brothers contrived to inform their family of their condition, and the poor people at Alcalá at once strove to raise the ransom money, the father disposing of all he possessed, and the two sisters giving up their marriage portions. But Illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness Mami had found on Cervantes the letters addressed to the King by Don John and the Duke of Sesa, and, concluding that his prize must be a person of great consequence, when the money came he refused it scornfully as being altogether insufficient.

The owner of Rodrigo, however, was more easily satisfied; ransom was accepted in his case, and it was arranged between the brothers that he should return to Spain and procure a vessel in which he was to come back to Algiers and take off Miguel and as many of their comrades as possible.

This was not the first attempt to escape that Cervantes had made. The second attempt was more disastrous. Wild as the illustrate how mother teresa demonstrate her kindness may appear, it was very nearly successful.

The vessel procured by Rodrigo made its appearance off the coast, and under cover of night was proceeding to take off the refugees, when the crew were alarmed by a passing fishing boat, and beat a hasty retreat.

On renewing the attempt shortly afterwards, they, or a portion of them at least, were taken prisoners, and just as the poor fellows in the garden were exulting in the thought that in a few moments more freedom would be within their grasp, they found themselves surrounded by Turkish troops, horse and foot.

The Dorador had revealed the whole scheme to the Dey Hassan.

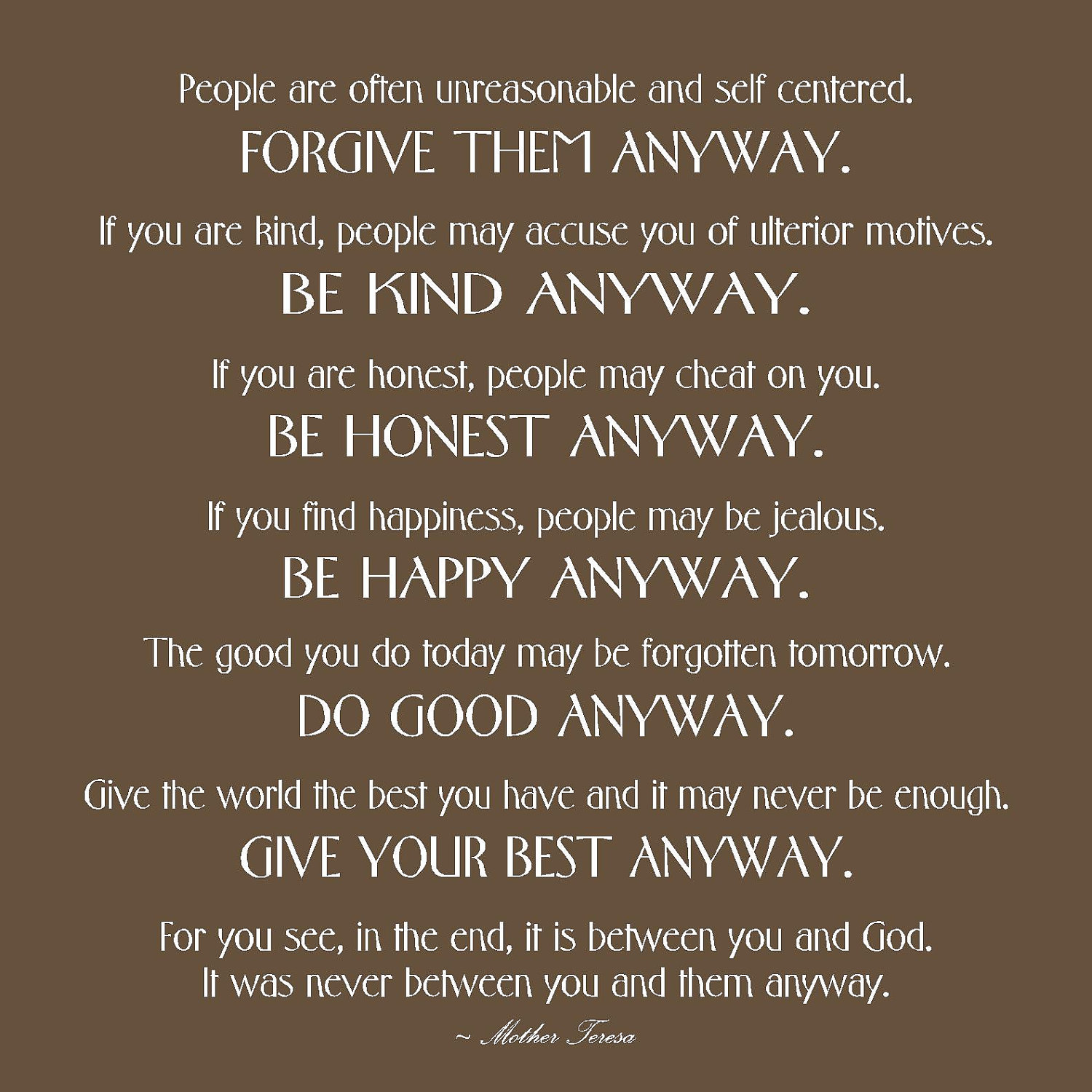

Inspiring Quotes by Mother Teresa on Kindness, Love, and Charity

, time: 15:45

Welcome to the inaugural Publishers Weekly U.S. Book Show Grab a Galley. We’re excited to share with you some of the buzziest titles hitting the shelves this fall. We’ve assembled quite the Aug 26, · Her name was Aldonza Lorenzo, and upon her he thought fit to confer the title of Lady of his Thoughts; and after some search for a name which should not be out of harmony with her own, and should suggest and indicate that of a princess and great lady, he decided upon calling her Dulcinea del Toboso—she being of El Toboso—a name, to his mind Física o Química is a Spanish teen drama television series produced by Ida y Vuelta Producciones for Antena 3 that was originally broadcast from 4 February to 13 June In this series they talked about topics such as: drug, suicide, racism, domestic violence, rape, sex, virginity, teenage pregnancy, homosexuality, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, cheating, forced marriage, same

No comments:

Post a Comment